This page is located at: http://www.ncsall.net/?id=176

Relationships Count

Relationships Count

Transitioning ESOL students into community college takes collaboration and personalized services

by Jeanne Belisle Lombardo

A major concern in working with students of English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) is advancing their language skills significantly before they enter community college. They want to enter college at a high academic English as

a Second Language (ESL) level or move directly into credit-bearing courses leading towards a certificate or degree. Rio Salado College,

one of the ten colleges in the Maricopa Community College District (MCCCD) in Tempe, AZ, administers an adult basic education (ABE) program that serves nearly 5000 ESOL students a year. In response to the need to move academically capable ESOL students into postsecondary educational and training opportunities

in the MCCCD system, the college established a transition program in the summer of 1998.

Rio Salado College had long recognized the need for a formal transition program. In 1998, the Arizona State legislature decided to support such a program with state funds. The Legislature changed the existing regulatory language and allowed community colleges providing ABE services in Arizona to collect Full Time Student Equivalent money (FTSE) to support transition programs. FTSE (pronounced "footsie") is state aid money paid to the community college based on student hours. With its funding assured, the Transition Program at Rio Salado was launched with two program advisors, a half-time counselor, and a data entry clerk.

This structure was expanded a year later to include a full-time coordinator, three full-time transition advisors, and an administrative secretary. One of these advisors works exclusively with ESOL students, recruiting a total of about 150 new students a year, of whom about half are ESOL students. Most of Rio Salado College's ESOL transition students are Hispanic, predominantly Mexican, 50 percent male and 50 percent female, single, and between the ages of 21 and 36. Some older students are married and have one or two children. In addition to Mexico, students come from other Latin American countries, Asia, Europe and the former Soviet Union, Africa, and the Middle East. In contrast to many lower-level ESOL students, most ESOL Transition Program students are better educated in their country of origin, having finished at least high school. More than half are employed, at least part-time, and most take one or two classes a semester after they complete the transition. Many are recent arrivals to the United States and show enthusiasm for the opportunities represented by the program. With few recruiting problems, the focus is on better preparing them for college.

|

ESOL / ESL In this article, English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) is used to refer to the classes in which students are enrolled when they are recruited for the program. English as a Second Language (ESL) is used to refer to community college classes. These are credit courses on a par with developmental level classes and as such do not count towards graduation requirements. |

The three Transition Program advisors form the backbone of the program. One focuses on recruiting students from approximately 20 to 25 advanced ESOL classes, spending about 30 percent of his time on this. Visits to classes are spaced so that the advisor visits each class about once

a month. The advisor adjusts the frequency of visits based on the readiness of students at a particular site. Variables include when the students started in that level, whether or not they have participated in a Transition Program workshop yet, individual motivation and readiness, and the speed at which students are progressing in their ESOL studies. The students are in classes across Maricopa County; the farthest site from our central office is a 30 to 40 minute drive away on the freeway.

Relations with the ESOL Program

The cooperation and support of the ESOL teachers are essential to the program. Teachers and the ESOL Transition Program advisor collaborate naturally. Aside from the in-service trainings and occasional special trainings focusing on tips for preparing ESOL students for academic writing, teachers are not paid for time outside their teaching duties. Most, however, keep a supply of Transition Program fliers and brochures on hand and distribute them to students who have recently arrived in their classes, refer potential candidates to our program, and communicate students' strengths and areas where improvement is needed. We find that students whose teachers work closely with us are better able to transition.

The Transition Program advisor recruits from the upper level ESOL classes using a PowerPoint presentation. This presentation covers the programs offered at the MCCCD colleges; the support services available, including child-care; ways to prepare ahead of time; facts to dispel fears that students don't belong in community college, such as statistics on the number of women, minorities, and students over 30 who make up the student population; and recommended timelines. It is given in English, since students ready for transition must function in English sufficiently to navigate the system. It is, however, desirable for the Transition Program advisor working with ESOL students to be able to speak Spanish, since so many of our ESOL students are native Spanish speakers. Not only does this give the advisor insight into the challenges these students face, it also allows him to provide information to many of the beginning ESOL students to encourage them to transition in the future.

We have found that more students go on to take college classes from sites where teachers take a proactive role in the transition process and work closely with the Transition Program advisor. It also helps tremendously when the advisor has experience teaching ESOL, ESL, or even English as a Foreign Language (EFL). We share information via the ABE Program newsletter, the Transition Program newsletter, sessions at the biannual in-service trainings for instructors, and letters sent out by the Transition Program coordinator. One of the best ways that teachers and the advisor share information is through one-on-one conversations during site visits. This is especially effective when the advisor knows the content of the college classes into which the students will transition.

Relationships with Students

Transition services are offered to all ESOL students once they have reached the high-intermediate to advanced level in ESOL. After a classroom visit by the Transition Program advisor, students are invited to contact him; appointments are held at a location convenient to the student. Students are considered Transition Program participants when they are still taking ESOL classes but begin to have one-on-one advisement, usually in the semester before they enroll in a college class. Once they enroll in an ESL class on a college campus in the system, they generally stop taking ESOL instruction, although some still prefer to take non-credit ESOL as well for the extra opportunity to learn what these classes provide.

The Transition Program advisor meets one-on-one two or three times with a student. This is flexible, however: the advisor is accessible on an as-needed basis. A first meeting typically includes a discussion of the student's goals, motivation, and preparedness for taking college classes. Together the student and advisor complete initial program paperwork. The student will have been tested in his or her ESOL class and the advisor will have the results. If the scores indicate that the student is academically ready to participate in the program, arrangements are made for the student to take the college English language placement test (CELSA).

A visit to the college for the CELSA, coupled with assistance with admissions and a short tour of the campus, constitutes a second visit. The advisor helps with class selection at this time and steers the student to registration services. Students attending the same college or coming from the same class sometimes do this together as a group. Students can meet individually with the advisor another time to discuss the particulars of their situations.

Gauging Readiness

After the first year of the program, we realized that we needed to have a systematic assessment of students' readiness for college classes and English language skills, in particular writing and grammar. The advisors had been giving the CELSA test to gauge readiness, but found that the scores were not a good determinant of it. Moreover, advisors had ethical concerns about using the test multiple times with each student, since it can only be given twice in a one-year period. Instead, we chose as an assessment the language portion of the Test of Adult Basic Education (TABE: Survey Form 7, Level D). The TABE gives a good indication of advanced ESOL students' ability in grammar and writing. Because it is also prescriptive, it is useful in determining areas in which students need remediation. Students are required to score 18 out of 25 questions on the TABE to be eligible for the Transition Program. This places them at an eighth-grade level for native English speakers.

After being accepted into the program based on their TABE scores, students begin a systematic study of grammar and prepare for the CELSA. The advisor provides students with CELSA study guides and encourages them to take a free Transition Program writing workshop. These are offered three times a year at our central site, the Adult Learning Center, and at least three times a year at other sites, and run from five weeks to 15 weeks, depending on the site. The workshops meet once a week for two hours and were designed based on observations of classes in upper-level ESL grammar, writing, and reading and a review of the texts used in those classes.

At smaller sites, where it is impractical to offer a workshop, the Transition Program advisor works closely with the ESOL teachers, encouraging them to provide challenging exercises for students participating in the Transition Program, and to assist with transition journal writing. Journals not only serve as a tool for assessment and advisement, but also provide a dialogue between advisor and students. In the past, the advisor reviewed students' journals, but now we encourage teachers to review them. The Transition Program also provides materials for independent study for students who are not able to take a writing workshop. Students complete the materials in the Independent Study Program (ISP) packet of reading and writing assignments, and the transition advisor reviews them.

Relations with For-Credit Staff

Rio Salado College administers the ESOL Program but it is the only college in the system that does not offer a for-credit ESL program. ESOL students therefore transition into one of the nine other colleges. Establishing and maintaining good relations and communication with staff at these colleges, in particular in Financial Aid, Admissions, Advisement, and among ESL faculty, is critical to student success. In the program's early days, the coordinator actively established relationships. She met with the appropriate people on each campus to explain the Transition Program's objectives. The coordinator tracks changes in personnel on the campuses, makes periodic visits, updates lists for the team, and keeps our contacts informed about program activities and concerns.

The importance of this connection can be seen in each step of the transition process. For example, the Transition Program provides its students with small scholarships, which cover up to six credits of college tuition. This allows students time to adapt to the more academically demanding environment on a college campus without worrying about the cost of tuition and gives them time to explore other avenues of financial assistance. Students begin to pay their own tuition for higher-level ESL or general classes that they can apply towards a certificate or degree. The Transition Program, through its contacts in the Financial Aid departments, provides support in this area as well. The program coordinator keeps current on scholarship opportunities open to students and the advisor refers students to our contacts in Financial Aid offices on the campuses.

Without a strong relationship between the Transition Program and these important departments on each campus, the paperwork required in the scholarship process could easily be a deterrent to student enrollment. The personal connection with staff at the colleges makes it possible to address potential problems quickly and effectively. It also promotes a feeling of good will between Rio Salado College and the sister colleges in the district and contributes to the positive experiences of our students as they transition and adjust to campus education.

Challenges

By far, the biggest challenge has been tracking students. Our ability to track students across semesters and years has improved with the development of a program-specific Access database, which has the support of top management at the main campus. This database tracks students from the time they begin advisement in the program and through their progress at a campus until they skip a semester. We use the Maricopa District's student tracking mechanism, Student Information System (SIS), to retrieve grades and track student withdrawals or drops each semester. This information is input into the Transition Access database.

Collaboration with the Admissions and Records departments on campus is very helpful. Although Rio Salado College is in the same system as the other colleges, each maintains some autonomy, which is reflected in access to certain records. A contact in the Admissions department can help us gain access to information that might be hard to retrieve otherwise. Other challenges we have successfully addressed have included requiring students to understand the college's drop and refund policies, or requiring students to finish the ESL pathway at college before taking a computer class there.

Indicators

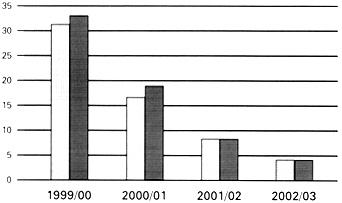

How does the Rio Salado Transition Program know it is effective in recruiting, enrolling, and retaining ESOL students into community college? One way we gauge success is to look at drop/withdrawal rates and pass/fail rates over the life of the program. There has been a dramatic and consistent decline over the last four years in the drop/withdrawal rate of ESOL Transition students and a corresponding increase in the pass rate. From FY 1999/2000 to 2002/2003, the drop/withdrawal rate fell from just over 30 percent to less than five percent. The graph below illustrates this, with the first column representing number of students and the second column the number of classes.

Drop/Withdrawal Rates for ESOL Students

A look at the pass/fail rate is also revealing. In the first year of the program, 73 percent of college level ESL classes taken by transition students were passed. That went up to between 95 and 100 percent each year thereafter. Anecdotal evidence and feedback from the colleges suggest that the program is placing better prepared students into college classes. Some students are continuing with their studies through multiple semesters, some of them are reporting the achievement of an Associate's degree, and a few are going on to take university classes, while others are improving their immediate job situations.

What We've Learned

From the advisement process to the collaboration with ABE instructors and with student services contacts on the various campuses, our personal approach has fostered communication between all involved, which we think contributes to the success we're seeing. Another plus has been scheduling flexibility, which enables transition advisors to spend as much time as is necessary with students. This allows us to be far more effective in building relationships with and supporting students as they navigate all aspects of college.

The other key to the high retention of these students once they make the transition to college classes is the level of preparation they receive in the semester leading up to their first class. The team attributes much of the success experienced by our students to this aspect of the program. By the time students take high-level ESL grammar classes, they have met numerous times with the Transition Program advisor, have taken the TABE assessment, have been given the opportunity to do individualized study and take one or more writing workshops and understand the requirements of college class.

As Rio Salado's ABE Transition Program moves into the future, the team will continue to assist ESOL students wishing to achieve a post-secondary education. Along with the writing workshops, the Program has begun to offer workshops in basic computer skills and has explored opportunities to partner with local libraries where students will have access to computers at no cost. For those who are looking ahead to university study, the Transition Program coordinator has established new contacts at Arizona State University, which will facilitate the transfer process to a four-year college. The team will also partner with the GED arm of the program to provide expanded services to ESOL students who wish to get a GED before transitioning into college classes. The Transition Program has coordinated the use of GED graded readers in selected upper level ESOL classes. This helps prepare those students for the transition into GED and also provides additional academic practice for all students.

Looking back over the four years, we can offer this advice. Try new approaches! Experiment with workshops and study programs. Tailor schedules to your students' needs. Be flexible. Talk to college contacts to get a look at what is being done for ESL students on the campuses. Think how you can use your technology creatively. Think how you can use other aspects of the larger program with your ESOL students. And build those relationships. In the long run, they really do count.

About the Author

Jeanne Belisle Lombardo has taught ESL, ESOL, and EFL in California, Arizona, Japan, and France. She now coordinates the ABE Transition Program at Rio Salado College in Phoenix,

AZ.