This page is located at: http://www.ncsall.net/?id=198

Not by Curriculum Alone

Not by Curriculum Alone

This ABE program found that the class schedule needed to change to support curriculum changes

by Mary Lynn Carver

Over the past decade, as a teacher of beginning level adult basic education (ABE), I rarely had a semester in which I didn't feel frustrated. The students just weren't "getting it." I work for the College of Lake County (CLC) in Grayslake, Illinois, and for the Waukegan Public Library Literacy program's Adult Learning Connection (ALC). Adult Learning Connection is a coalition of the Waukegan Public Library, CLC, and the Literacy Volunteers of Lake County. For years, CLC's ABE classes followed a very general curriculum. CLC developed a loosely organized set of competencies in 1995, but never turned them into a full curriculum. We teachers were free to be as creative as we wanted, with minimal guidance as to specific materials or methodologies. We used the best methods available to us, but we all had high drop out rates and saw little measurable student progress, especially with learners who tested into our beginning level (0.0 to 3.9 grade level equivalent on the Test of Adult Basic Education [TABE]). We wanted to address the drop out rate and find a more effective way to serve beginning level reading students.

Teachers were not the only ones feeling frustrated. The ALC-trained volunteer tutors, who worked one on one with students or in classrooms, expressed concern that their students were not progressing quickly enough. The literacy program staff decided to start looking for ways to improve, thereby embarking on a reflective process in which we are still engaged.

Learning from Others

We started, about eight years ago, by talking to people who seemed to succeed where we were failing. At the Illinois

New Readers for New Life conference, we connected with students from other programs who had success in learning to read. We participated in electronic discussion lists on the Internet and began networking with other programs. An awareness of what we might be missing began to grow. We met John Corcoran, author of

The Teacher Who Couldn't Read, on a guest author visit at the Waukegan Public Library. John overcame his decades-long struggle to become a reader using the techniques featured in the Wilson Reading System methodologies and the Lindamood-Bell Learning Processes. He attended our annual tutor conference as a guest, and directed us to Meg Schofield, of the Chula Vista Public Library in California. Meg is a literacy practitioner who was trained in both the Wilson Reading System and the Lindamood-Bell Learning Processes. She has effectively translated both those systems into her practice with adults who have low literacy levels. Another former literacy student who has become an activist in the field of adult literacy, Archie Willard, also pointed us towards the Wilson Reading System when we met at a conference later that year.

ALC staff began to read the work of Dr. Reid Lyon, Chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. In a 1997 address before Congress, Dr. Lyon stated: "What our NICHD research has taught us is that in order for a beginning reader to learn how to connect or translate printed symbols (letters and letter patterns) into sound, the would-be reader must understand that our speech can be segmented or broken into small sounds (phoneme awareness) and that the segmented units of speech can be represented by printed forms (phonics). This understanding that written spellings systematically represent the phonemes of spoken words (termed the alphabetic principle) is absolutely necessary for the development of accurate and rapid word reading skills." Since his research focuses on how a beginning reader acquires the reading process, we wondered if it would apply to adults. In 1995, the research on how adults learn to read was sparse at best, so we were exploring new territory when it came to what might work for them. The research on children provided a glimpse into what we wanted, but it wasn't enough.

We asked our students: "What do you think we aren't doing?" As coassessors of their learning, they knew what they didn't know, which was how to "figure out words right." As we learned more about the subskills of reading and specific techniques for teaching those with learning disabilities, we began to understand what they meant. Financed by a combination of personal, grant-funded, and volunteer donations, various staff members participated in such training opportunities as attending sessions on the Orton-Gillingham method, a phonemics-based program; participating in an overview of the Wilson Reading System, a multisensory, phonemics-based program organized around the six syllable types; and spending two weeks in California at a training on the Lindamood-Bell system, useful for helping students acquire an awareness of individual sounds in words.

Over the years, staff turned to the National Institute for Literacy's web site

(www.nifl.gov) for reliable resources on reading research; we also scoured professional reading and learning disability journals such as the

Journal of Reading and Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. We looked at information provided by Equipped for the Future and NCSALL's

Focus on Basics. One staff member participated in the "Bridges to Practice" training offered by the National Adult Literacy and Learning Disabilities Center, which covered assessment of learning disabilities, planning, teaching, and fundamentals of the teaching and learning process.

Changes Begin

In 1997, the ALC offered experienced tutors two 2-day seminars with Meg Schofield. She came to Illinois from California in the middle of a Chicago winter to share her expertise on specific strategies to incorporate phonemic awareness into our teaching. Four of our literacy program staff are also employed by the college to teach the beginning level ABE classes. This creates consistency between the two organizations and also coordinates much of what the ALC does with the CLC ABE program. About 20 volunteer tutors and two or three CLC ABE teachers who taught the lowest-level ABE classes and ALC staff attended the sessions. Our goal was to pull together everything we had learned to this point and effectively revise our program so that we could move students from one-on-one tutoring sessions into our ABE classes. We wanted the learners to be able to transition smoothly and have consistency between the literacy program methods and the techniques used in the classes. At that time, we were looking at phonemic awareness as an additional tool to use in the classes. The reaction of the tutors to the training was positive and their enthusiasm and conviction that this was the missing piece of our instruction helped the learners accept the "new" methods we started to incorporate.

Two or three years later, we realized that a curriculum change needed to be our next step. The ALC tutors and staff were having success with their individual students. It was time to expand. One of the first changes ALC staff incorporated was how we think about what we teach (in class and in tutor training). Since 1997, we have been working to incorporate the development of phonemic awareness skills into the beginning reading (lowest) level classes and into the new tutor training program. With input from teachers at each level, we are beginning to implement these skills into the subsequent (midlevel) classes, another step towards our original goal of smoothing transitions for our learners.

The college agreed that it was necessary to update the curriculum for all ABE and General Educational Development (GED) levels. We now have three curriculum teams, each serving two levels of class. Each team meets with the teams from the levels above and below them to discuss what skills should be covered at each level, what content is appropriate at each level, and what methods should be used at each level. The ABE curriculum teams consist of ALC staff who are teachers, and two midlevel ABE teachers who attended either the Meg Schofield or Wilson Overview training. They understand the underlying reasons behind what we are trying to do. The third team is made up of pre-GED and GED teachers who automatically have a more defined curriculum because of what they teach. By the time students reach those GED class levels, they should not need the same focus as lower ABE class levels.

Implementing Change

Going from being able to teach whatever you want to becoming structured and consistent has been a big change for teachers and tutors. Many students come in wanting to get their GED and find out that first they must learn to be better readers. It is still hard for me as a teacher to say, "You aren't ready yet, let's try this step first." Not everything has changed, however. Although my approach is more structured now, I still base my lesson plans on content in which my students have expressed interest. First we cover concepts, skills, and vocabulary, and then we apply it to that day's material. I get help from colleagues: with a small core of teachers, we find it easy to meet and brainstorm together, share materials and techniques, and help each other to refine ways in which to present different concepts.

Some learners are reluctant to try the multisensory techniques we now use, and a few students each term drop out. They often decide to try again. If they test back into my class, I try to persuade them to stay and give these techniques a try. Other students tell them that these techniques are the best things that ever happened to them. The reluctant participants usually find that this approach to learning makes sense and provides them with the skills they need in order to progress.

Changes to Assessment

Some students come to us through the college's placement testing system, and many are referred to the literacy program by their local library, via the Illinois Employment and Training Center, or by word of mouth. ALC staff administer the state-mandated Slosson Oral Reading Test (SORT). Based on our new knowledge, if a student seems to struggle with vowel sounds and decoding, we decided to administer a modified version of the Wilson Assessment of Decoding and Encoding (WADE). This gives us an idea if the student understands sound/symbol relationships. If they do not understand them, we match them with a specially trained "Quick Start" tutor, who works to familiarize them with the alphabetic principle, short vowels, and consonants. When a student has an understanding of how the sound/symbol system works, we match them with another tutor. Our goal is to move them eventually into a beginning-level ABE class. We find that students experience the most success if they come into class aware of the 44+ phonemes, six syllable types, and other fundamentals of the Wilson and Lindamood systems. When students leave the beginning reading level, they should have mastered all 44+ phonemes and closed syllables, and be familiar with the other syllable types. For some students, this may take only eight to 16 weeks. For others, who may have undiagnosed learning differences, it may take years.

In the next three class levels, (roughly equal to levels 2.0 to 7.4 on the TABE), students continue to master the remaining syllable types, prefixes, and suffixes. For students continuing from the beginning reading level, it provides an easier transition; for newer students, it is an introduction to the concepts. Included in all levels of curriculum are strategies for reading, writing, infographic interpretation, sight words, critical thinking, and computer skills. Students apply the phonemic awareness and word structure principles to reading materials in all class levels.

Delivery System Change

The ABE classes offered through the college are traditionally 48 or 96 classroom hours per semester. This translates to two classes a week, for three hours each, for eight or 16 weeks, with a five-day gap between weekly classes. By the time beginning reading level students returned the next week, they had forgotten much of what was covered. The Lindamood-Bell model requires a

minimum of two hours a day, for five days a week, for extended periods of time. A curriculum change wasn't going to be enough; we needed to re-examine our delivery system. While we could never provide the intensity required by Lindamood-Bell, we wondered if a four-morning format would improve our learners' success rates.

Beginning in the fall semester of 2002, for one beginning reading class section, the college approved a pilot class with an intensive format. We changed the morning beginning reading level class to a six-week, four-morning per week, two-hour per day session. Since we still had to work within the 48-hour parameters, we requested two six-week sessions per semester for a total of 96 instructional hours.

Results

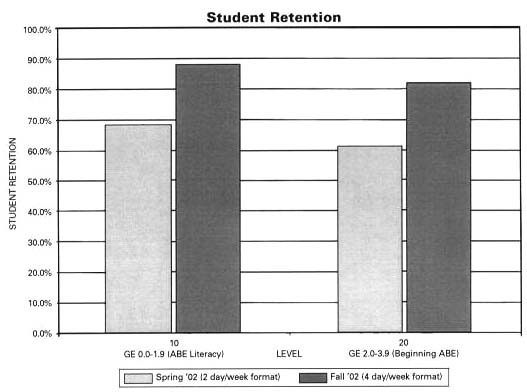

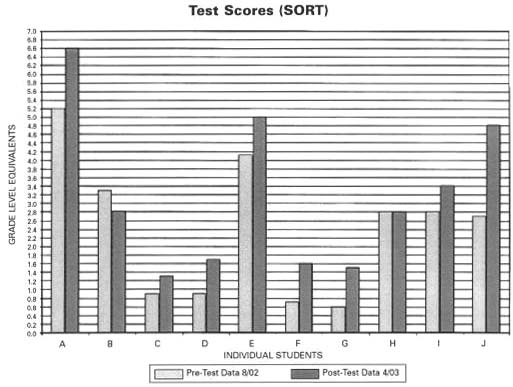

These changes seem to have been successful. The attendance rates of the students have increased (see Student Retention graph). The standardized SORT assessments have shown improvements over the test class's six month period from September, 2002, to March, 2003 (see Pre/Post test graph). Aside from quantitative measurements, the learners give us feedback on how well this format is working for them. Coming every day gives them a feeling of belonging, in addition to providing repetition and reinforcement of what they are learning. The work they do in a structured, predictable format helps them to build on their own achievements. Their self-confidence has increased as evidenced by their writing and reading. They write about being more confident at work, helping their kids with homework, even volunteering to read in public. These are students with 0.0 to 3.9 reading levels (as measured by the TABE), who have struggled for decades to hide what they didn't know. They are now willing to take more risks with their learning, and they decide what topics we will learn about next. They are truly partners in their own educational process.

It has not been easy to implement such a substantial change. The amount of material we want staff and volunteers to know requires significant training time. Three hours of our program's initial tutor training introduces phonemic awareness. Tutors are also offered phonemic awareness workshops as part of a series of monthly tutor in-service training sessions run by ALC staff. Our staff has learned that the volunteer tutors need continuing support to facilitate or maintain confidence and consistency in their tutoring. Many tutors start out in a classroom with one of the paid instructors for extra training and practice, before being confident enough to work one on one with a student. We have invested in books and materials, including sets of the Wilson Reading System, magnetic journals, sound cards, and 8 x 11 inch white boards and markers for classroom use.

Developing a curriculum that works is an evolutionary process. Eight years ago, we had no long-range plan. ALC was committed to implementing a new program component and, as resources became available, took each subsequent step. We have found that direct, systematic teaching of phonemic awareness and word structure seems to be an essential component of ABE curriculum. A change in schedule was also important. We are currently mapping out our new curriculum. Our final document will provide the skills, strategies, methods, and materials appropriate for each level of student instruction, and be the basis for teachers to plan their lessons. We hope that specific skills and competencies will be taught using student-generated topics of interest. Even when it is done, we will continue to attend professional development events and adult literacy conferences and incorporate new information as it becomes available.

Students have repeatedly remarked, "Why didn't someone show us this a long time ago?" We remind them we are all learning together. A successful curriculum is not static. It must keep changing as we learn new ways to present information and as we build on new research findings. Since including phonemic awareness in every aspect of my teaching, and since changing our calendar, I have not felt as frustrated. The students are getting it. We are all disappointed that the end of term comes so quickly.

References

Corcoran, J., Carlson, C. (1994). The Teacher Who Couldn't Read. Colorado Springs, CO: Focus on the Family Publishers.

The National Adult Literacy and Learning Disabilities Center (1999). Bridges to Practice: A Research Based Guide for Literacy Practitioners Serving Adults with Learning Disabilities. Washington, DC: National Institute for Literacy.

www.nifl.gov/lincs

The Orton-Gillingham Program, Academy of Orton-Gillingham, P.O Box 234, Amenia, NY 12051-0234.

The Wilson Reading System, Wilson Language Training, 175 West Main St., Millbury, MA 01527-1441; telephone (508) 865-5699; fax (508) 865-9644.

http://www.wilsonlanguage.com

LiPS- Phoneme Sequencing Program, Lindamood-Bell San Luis Obispo, 416 Higuera Street, San Luis Obispo, CA 93401; telephone (800) 233-1819; fax (805) 541-8756 http://www.lblp.com

See Focus on Basics Volume

5A, August, 2001, on First Level Learners, for more information on the methods the CLC incorporated into its curricula.

About the Author

Mary Lynn Carver has been a part-time faculty member at the College of Lake County, Grayslake, IL, since 1990. After completing a Masters in Adult Education in 2001, she joined the Adult Learning Connection (ALC) as the Assistant Literacy Coordinator at the Waukegan Public Library. On the ABE curriculum development team for CLC, she is on-site staff at the Library's Adult Learning and Technology Center in Waukegan and offers monthly tutor training workshops for ALC volunteer tutors.

Acknowledgment

The author offers deepest gratitude to Paula Phipps and Barbara Babb for all their information, input, and patience in the development of this article.